Spotlight: Adam Keay

It is a pleasure to be able to spotlight the work of artist Adam Keay in this new series. Two of Adam’s artworks have recently become part of the artPost21 Collection. For those who are not aware the Collection has been developing for 20 years now—it is an archive and index of movements, friendship, kinship and shared ideals among artists and friends. It was solidified by a small gift and is maintained in a modest but loving way. It now contains several hundred works that seek to focus on the concept of ‘dreamwork’ - a form of social imagination that encourages us to look beyond the ordinary; to consider the possibilities that emerge from within the interstices—of the picture plane; of history, and beyond.

Can you tell us a little bit more about your artistic story. Where do you live and primarily work? And what does your ritual of making art primarily look and feel like?

I am a painter who lives and works in York, UK. I began taking painting seriously in my teens, becoming interested in artists such as, Alberto Giacometti and Francis Bacon in particular. After school I studied Fine Art and English Literature at University and did an MA in Cultural Theory. Books, films and music have always fed into my painting.

My studio is in the attic of my house, which allows me to fit short sessions of painting in around work and family. This works well for me as I can get to the studio quickly if some time suddenly becomes free. I also prefer to work alone, as opposed to a shared studio set-up, as I like to lose myself in the work. Putting on music is a big part of the ritual of making art for me. I then generally begin by orientating myself within the studio - tidying, looking, assessing, preparing – all this allows a natural lead into the more ‘sit down in front of the easel’ type process of painting. The feeling I get from the ritual is one of sanctuary – of being ‘away from the world’ and in my own space, of accessing the flow state where the paintings can evolve.

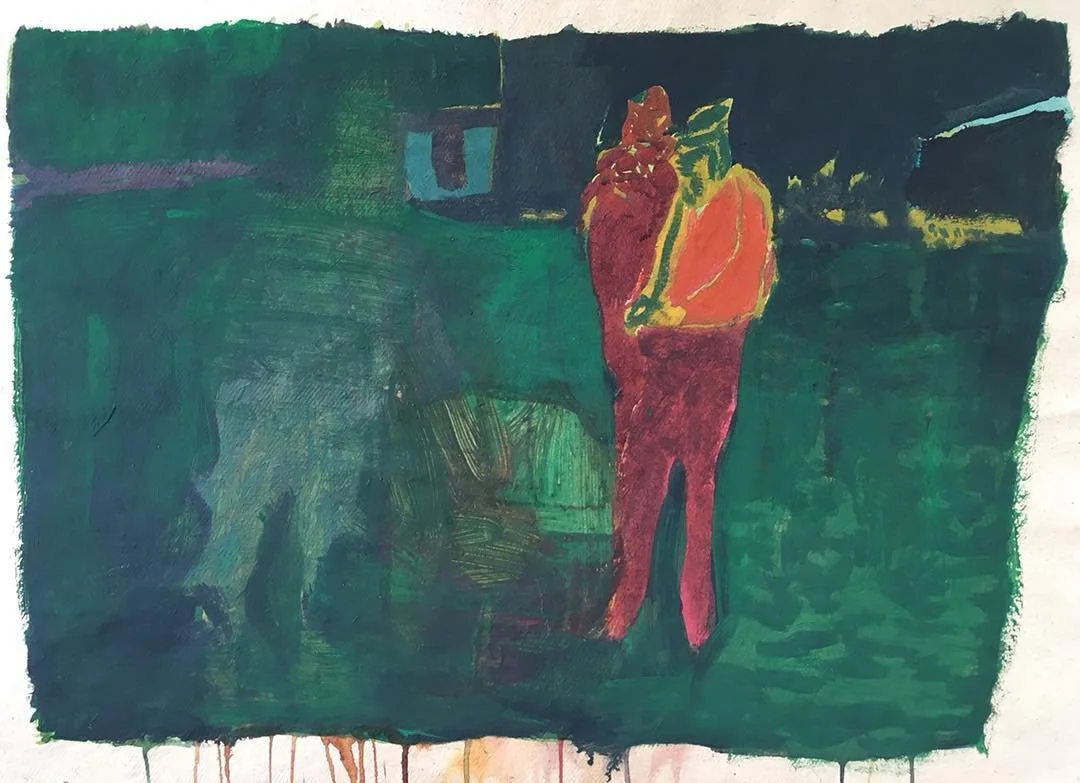

Adam Keay, Twitcher, Ink and Acrylic on paper, 84cm x 59cm, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and the artPost21 Collection.

How much does the context of living in York affect the and shape your work?

I have lived in York on and off since 1995 and although it’s not a city known particularly for contemporary art, I think the people I have met in York have certainly helped to shape my work and practice over the years. I worked as a projectionist here for many years, also curating a small arts space in a cinema-arts venue. The people I was around during that time had a big influence on me. There have always been artists in York who have a passion for contemporary art and painting and we have encouraged each other through discussion, collaboration and small exhibitions. I think feeling slightly ‘outside’ the predominant scenes as they were, but also meeting likeminded people, has encouraged me to make work which seems right to me in the contemporary context, despite feeling that the art world is ‘over there’ [somewhere]. This feeling has perhaps continued the one I had growing up where our house was located between towns, isolated and on the outskirts, which I do believe has influenced my work (for example the regular feature of figures isolated in landscape, the use of images inspired by escape into films etc).

Your picture planes are rich, layered, and then stripped back, and saturated once again, as if you’re in a constant conversation with colour, material and form: Can you talk us through what appears to be process? Perhaps I have it all wrong. Do you begin with a composition in mind, or does the pictorial field emerge from a site of pure feeling?

The composition starts with a found image, generally a film still, but sometimes a photograph or image from a book. The image will be one that I find interesting or drawn to in some way but may not always end up being recognizable in the final painting. Sometimes a good image doesn’t translate into a good painting, if there is not a way in.

Quite often I will make a drawing or monoprint from the film still or photo/image. I might also manipulate the image before this drawing is made (for example by changing the aspect ratio). The drawing might include unexpected forms or marks that can lead me to consider different ways into the painting, which I had not anticipated.

I prepare the surface of the canvas or board carefully with around 7 layers of priming, which is then sanded. I like the surface to be removed from the weave of the canvas or the natural surface of the board. Once I have the drawing or final image ready, I then project this onto the canvas or board. My process includes both automation – the trace of the drawing, the projection of the drawing - and then the more intuitive use of paint, through which the painting evolves.

My figurative paintings often build to a certain point and I then partially erase or deconstruct them (for example through rubbing down with a cloth, sanding, or painting over with a watered-down paint).

I then rebuild by taking note of the elements of chance that have been brought in through this process and use these as signposts and markers for ways forward in the paintings. I don’t like the painting to look too controlled or willed into position, hence the need sometimes to deface the painting.

I don’t want the painting to look ‘too good’ or ‘too finished’ (to paraphrase Philip Guston). At a certain point the painting is telling me what to do next. This can change from painting to painting – the issue for me is to tune into it. It is a back and forth with colour, material and form, trying to find a way through to an unknown place.

There are two marvelous works that have come in to the aP21 Collection. ‘Those days come back’ feels like a cartography of memory—almost as if time is parsed splayed across the entirety of the picture plane. You get that sense from the centrifugal figure whose eyes are doubled: suggestive of a multiplicity of conscious selves. Can you talk a little about how this work constellated for you?

Adam Keay, What We Lost In the Fire, Acrylic and ink on board, 81cm x 56cm, 2025

‘Those days come back’ is derived from a film still from a fairly unknown post-apocalyptic film. Occasionally it is obvious which film I have taken a still from but for the most part I like the source material to have an ambiguity to it. I like the capturing of a momentary fragment by using a film still, which might only be a 24th of a second of a film. The still for ‘Those days come back’ was manipulated in its ratio and then made into a roughly A4 monoprint, this was reduced to a projectable-sized image. I then projected [onto surface], and in this case, the outline was drawn onto board with a light yellow wash. Washes were built up and then thicker paint applied. The piece was then rubbed back and old elements re-projected and new elements projected. Some final areas of paint were put in as I felt the painting suggested.

The meaning is open ended and in this, I hope, gives space for the viewer’s own interpretation. David Lynch often spoke of wanting to take a viewer to a place in their head but not to be prescriptive about what they should feel. I have this view about my paintings. I do not have a particular intention beyond the making of the painting and feel that the interpretation is personal to the viewer. With most of my paintings, the image is interesting / stimulating / emotionally engaging to me. I feel compelled to draw it / paint it – the process happens and I allow the process to direct me. But when the painting is out in the world, I have no say in how the viewer should feel or interpret the work. Their own histories will dictate this.

Adam Keay, Those Days Come Back, Acrylic on board, 46.5cm x 46.5cm. 2022. Courtesy of the artist and the artPost21 Collection.

Adam Keay, The Nymphs, acrylic on board, 45cm x 45cm, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

Above: Gallery view of artist’s studio. Works in progress in 2026. Photos courtesy of the artist.

Adam Keay, Can You Amount to a Quarter?, Acrylic on board, 39.5cm x 32cm, 2025. Courtesy of the artist.